June is Dairy Month, and June 4th is #NationalCheeseDay. In celebration, check out this story from the archives about Fairview Swiss in Mercer County.

Story and Photos by Bill Zeiders

When Richard Koller, proprietor of Fairview Swiss, speaks with school children and asks them what can be made from milk, he gets the usual answers: ice cream, yogurt, cheese. But besides Swiss cheese, Koller’s family specialty, a few unexpected things can also be made from milk.

“Now we can make electricity and heat out of milk,” he said.

Koller has spent many years putting holes in cheese. Swiss cheese is the only type of cheese he makes at his plant in Fredonia, Mercer County. The company, started by his father John Koller, is the largest Swiss cheese manufacturer in Pennsylvania. Richard Koller joined his father at the plant after graduating college in 1975.

Over the years, they have modernized the business, and are now able to produce 7 million pounds of cheese per year. Upgrades to the plant range from computer automation and temperature controls to an anaerobic digester that can produce biogas used for generating electricity.

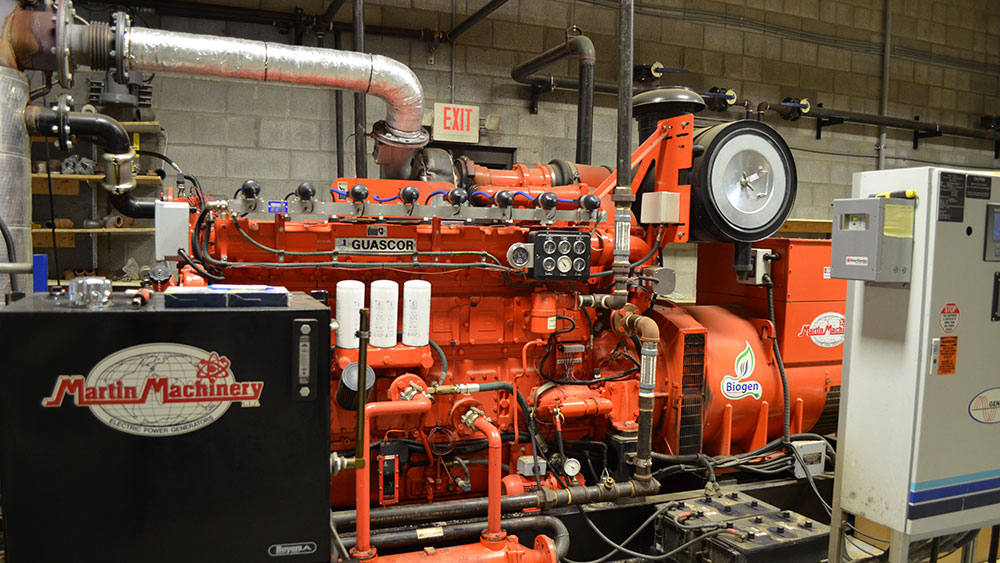

Koller, a Farm Bureau member, added his biogas system in 2009. Using an anaerobic digester and an engine that runs on methane, he converts what would normally be waste, leftover milk sugars called lactose permeate, into energy.

By reclaiming what would otherwise be byproducts of the cheese-making process and using them for energy, Koller has been able to generate about half of the electricity he needs to run his plant for the year. The system also treats the wastewater produced by the cheese plant.

“Clean water is returned to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, clean water going down the creek,” Koller said of the end of the process.

The process of making cheese, of course, begins with milk. In a gallon of milk, 88 percent is water. Cheese is made from the solids that make up the other 12 percent. It takes 10 pounds of milk to make one pound of cheese.

Koller gets his milk mostly from independent, local dairies. He uses grade A raw milk and pasteurizes it in-house. The green energy from his biogas digester comes in handy during this part of the process. Excess heat produced by the engine is used to heat wastewater and make steam. That hot water is pumped back into the plant to heat the milk during the pasteurization process.

Once it’s pasteurized, the milk goes into a centrifuge, which removes any dust or dirt and slightly reduces the butterfat content. Excess fat from the milk does not go to waste either. It is sold off and sent to be made into butter.

The milk is then ready to be turned into cheese. Fairview has five vats that can each hold 50,000 pounds of milk and produce 4,800 pounds of cheese. The milk is turned into curd over two to three hours. Agitators in the vats help the milk coagulate and bind the solids together. Other cheeses, such as mozzarella, would be easier and faster to make, Koller said, but swiss takes its own special kind of care.

“Swiss is particular,” he said.

A culture must be added to the vats of milk to make it cheese, and Swiss gets its own unique culture: propionic acid, also called “props.”. The culture has a similar job to yeast in bread. The agitators in the vats are reversed to cut and form the curds, and the culture is trapped inside.

The curds and whey are heated, giving Swiss its rubbery texture. The culture will remain active inside the cheese for up to six months, forming gas bubbles as it works. The elastic texture helps the cheese stretch around the bubbles and form holes.

A little more butterfat is skimmed out before the cheese is placed in molds and sent into an automated pressing and forming machine. The curd and whey is pressed for an hour and excess whey is drained. During this stage, the culture is hard at work knitting the curd together. The cheese is formed into 200 pound blocks.

The excess whey still contains useful proteins. Some of it is filtered, concentrated and sold to be dried and turned into protein powder that is used in animal feeds and protein supplements. Some of the whey is directed to the digester to produce methane fuel for the engine.

The blocks of cheese sit for 18 to 20 hours to allow the curd to ferment. The next step is brining, which is also an automated process.

“The majority is computer controlled. But we still do some things by hand,” said Koller.

The blocks of cheese are loaded inside salt brine tanks and brined for 24 hours. The brine cools down the cheese as it absorbs some of the salt and expels more whey. There are no holes on the outside of the blocks of Swiss because during the brining process, there’s a higher concentration of salt on the outside of the block. The salt kills the cultures, so it never makes it to the outside of the block. As the cheese ages, the salt content evens out.

The cheese is then packaged, and since Koller sells wholesale, the Swiss is left in large blocks. A plastic film is applied, which is sealed and then vacuum packed.

The packaging automation is 15 years old, and incorporates an industrial robot arm that was once used in car manufacturing. It’s been repurposed to lift cheese, which is very helpful, according to Koller.

“It used to be hand lifted, each 200 pound block,” he said.

During the aging process, the cheese is kept at 70 degrees. The heat reactivates the cultures and the holes start to form. It ages for about a month as the gas expands.

Because of the volume of cheese needed to feed hungry customers around the country, Swiss cheese’s style has changed since the 1970’s.

“One thing that’s changed since I started in the business, you used to look for quarter sized holes. Now, you want nickel or dime sized holes, because it’s easier to run through the high-speed slicers,” said Koller.

Cheese slices are made by running the cheese through a slicer that can produce three thousand slices per minute. Koller said that there are about seven high speed cheese slicers in the country running all the time to supply just one major fast food chain.

If you’ve ever had a sandwich with Swiss cheese at a popular burger chain, that cheese may have come from Koller’s plant. When a national chain restaurant decides to introduce one of those specialty sandwiches, it begins ordering the cheese supply well in advance.

The size of the holes in Swiss cheese are important because Swiss is different from other cheese in another important way. “Swiss is graded on looks, not taste,” Koller said. “It’s the only cheese like that.”

Swiss cheese is graded on the number and size of its holes, or “eyes.” The flavor of the cheese does not factor in, although, Koller added, taste is still important for business.

“Eventually, bad flavor will cause buyers to look elsewhere,” he said.

After aging, the cheese is moved to a cooling room. This stops the culture from forming more gas bubbles and continuing to expand.

“If it warms up, it can form gas, and then you’re in trouble,” said Koller. Once cheese is sealed and in storage, expansion can cause the packaging to break and the stacks of cheese to topple over.

At any given time, Koller has as much as 750,000 pounds of cheese in storage. Koller makes cheese year-round. The volume of milk available dictates how much cheese he makes.

According to its website, Fairview is committed to bettering the environment through sustainable practices and utilizing as much of their byproducts as possible. Farm Bureau members, like Koller, are leading the way in innovating responsible practices.

Fairview Swiss

What:

Wholesale Swiss cheese producer

Where:

Fredonia, Mercer County