Clinton County sheep farmer hopes to bring farming into the future.

Story and photos by Bill Zeiders

Daniel Dotterer is a man of two worlds. The Clinton County sheep farmer has had a career path that a lot of folks would find incredible to say the least. But his experience has led him to a project that he hopes will change the world and bring farming into the future.

Dotterer grew up on his family farm, and as a kid he worked hard. He gained a variety of skills and a solid work ethic. He also loved game shows and puzzles, and he learned how to juggle and ride a unicycle. He would often perform his circus acts at local schools and churches.

Dotterer attended Penn State to pursue a degree in vertebrate physiology, passed the MCAT tests and had medical school plotted out on his future roadmap. He took one acting class during his time at Penn State, but because he wasn’t an acting major he wasn’t allowed to act – only discuss the theories of acting.

He graduated on a Saturday in 2001, and without really telling anyone, he said, he left the farm for Los Angeles on the following Monday.

“We never left the farm, I never saw the ocean,” he said. “I’m not married, I don’t have any kids. I don’t want to wake up one day and be 70 and say, ‘Where’d it all go?’”

Despite not knowing anyone in LA, Dotterer relied on his work ethic instilled from years working on his family farm to find his way in a new environment. He compiled a list of 75 production companies, and the 75th one he called gave him a job for one day.

“At the end of the day they had me back for one more day. And the next day just one more day. And I just kind of caught on from there,” he said.

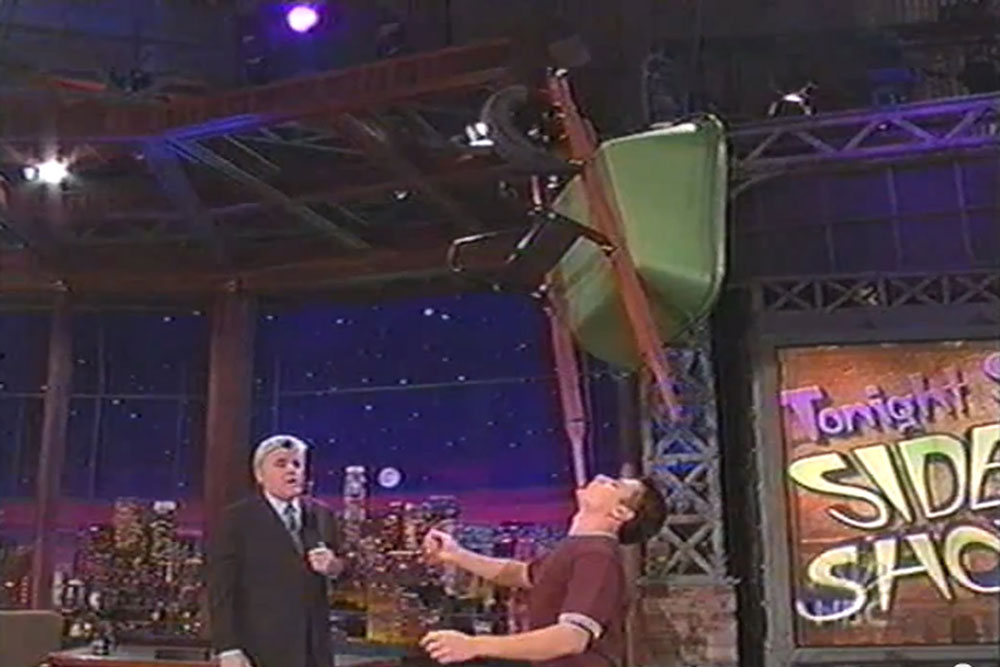

Dotterer was able to make a living acting, appearing in commercials, TV shows and some movies. He appeared on Jay Leno’s show and balanced a wheelbarrow on his chin. He rode his unicycle in a commercial for a restaurant chain. He did another commercial for mayonnaise, but Dotterer had a problem: He hates mayonnaise. He realized that as an actor he sometimes wasn’t able to fool himself enough to be believable to anyone else.

“I did acting when I was first out there, but I’m a horrible liar,” he said. “I found myself tweaking these scripts when I’d book parts and I’d slightly change things to make it more real for me, because if I didn’t I’d be awful.”

The experience led him to switch to writing and working on scripts.

“The writing is something I excelled in and made that transition, doing development on movies, reading scripts, reading books,” he said.

One of the first movies he worked on was Despicable Me, an animated movie that is known for its marketable co-stars, the little yellow guys in overalls called Minions. Dotterer saw an opportunity for the then up-and-coming production studio, and he wrote a script using the Minions. Since the available budget was scarce, he tapped into his farmer ingenuity and found a way to use what the company already had.

“The one idea that really worked with the script, I took characters and locations that were already animated, and I reused them in the script,” he said, explaining that doing so meant that two-thirds of the movie was already paid for. “They optioned that movie from me, and now total I’ve had 10 TV shows and movies optioned.”

Dotterer has also been working on game shows.

“I’ve always been good at games and puzzles, I always liked game shows. So I’ve actually won several game shows,” he said. “I won a car, it was one of those things where I won a couple (shows), and I actually kind of got into that world as well. One of the producers said, ‘You seem to know what you’re doing. Do you want to work on some game shows?’ For the last couple years as my day job I’ve been developing games and puzzles for game shows. Not exactly the most normal career path.”

But despite his success in Los Angeles, Dotterer never lost his passion for farming.

“A lot of people, when they move to the big city from the country, they forget who they are and where they’re from. In the entertainment industry, you’re just working job to job, so whether that’s a day, a month, six months or a year, then you have to look for your next job again. So I was always able to spend at least a month or two back home on the farm,” he said.

Then about four and a half years ago, he was introduced to an emerging technology – augmented reality – by a friend who works for Microsoft. At first, he was skeptical.

“He called me and said, ‘You’re the type of person that needs to see this,’” Dotterer recalled. “I said, ‘I don’t really play video games.’”

But that was virtual reality, and what Dotterer was shown wasn’t a video game. It was something completely different, he said.

“The first time I put the headset on my head in 2017, it blew my mind,” he said. “This is going to change the world, and I want to be part of that.”

According to Dotterer, augmented reality, or AR, is “overlaying of holographic information on the real world.” While it may be considered novel, the technology has been around for several years.

“In some ways, it’s just coming out. In other ways, it’s been out for a decade,” he said.

You may have experienced AR already on your smartphone. The technology has been employed in Snapchat and Instagram filters, as well as Pokémon GO, the popular mobile game in which players traverse the real world looking for animated animals visible only on their phones.

But the true potential for AR remains largely untapped.

“What I’m looking at is using this technology in agriculture,” Dotterer said. “Part of it is collecting and processing huge amounts of data and presenting it in a way that is easy to understand, to make informed decisions with it. But I see its uses in everything from animal management to crop management to even increasing veterinary access.”

Most of the AR technology can be used on a smartphone, but the advantage of having a hands-free headset or pair of glasses is what Dotterer thinks is the key to getting the most out of it.

“In the next year, everyone is coming out with their AR glasses: Samsung, Apple, Facebook, Intel, Amazon,” he said. “This is using new technology to allow us to do things better, quicker, faster than we were able to do before.”

While living in LA, Dotterer noticed the disconnect people had from their food more acutely. The average person lives in Los Angeles for about 22 months, he said, which makes for a stark contrast to rural Pennsylvania where some of the farm families have been living and working on the same land for more than 200 years. His own family farming legacy can be traced back to 1799, and his family has been on their current farm since 1819.

“People are so disconnected from their food now,” he said. “They have questions, they want answers.”

Dotterer believes the technology he is working on now will empower small and local farmers to connect more easily with consumers. Part of his vision includes using blockchain technology. If you’ve heard of blockchain before, it was probably in connection with cryptocurrency, like Bitcoin. But blockchain is technically just a secure storage system for data. When paired with RFID tags, there are many opportunities available for agriculture.

“A blockchain-based registry is a storage system, so unlike a lot of different storage types, it’s not centralized,” Dotterer said. “So say the information is held in eight different locations. If someone hacks into one location and tries to change that information, the seven other locations say, ‘Hey, something’s going on here, this is not right.’”

This system can be used to track commodities of any type, keep track of animal vaccines, or trace the source of an E. coli breakout, for example. The benefits include being able to respond to animal diseases and crises faster, to have confidence in the source of food, and to market more efficiently.

“Technology is heading that way, why not lead instead of follow? There’s a number of markets around the world that the United States can’t get in to because we don’t have any sort of animal tracking,” he said.

Dotterer’s vision sees a consumer wearing AR glasses, walking into a grocery store, picking up a product, and seeing information from the local farmer displayed next the product, which empowers both the farmer and the consumer.

Photo credit: Holly Cohick

“Farmers never really get any recognition for their work. Unless you’re at a farmers’ market, we never meet that consumer,” he said. “Now you’ll be able to go to the store and know that carton of milk came from that certain farm. They are connected to it and they’re supporting their community. People love that kind of stuff and they’re willing to pay a premium for that.”

Dotterer is now working on bringing his vision to fruition, and he’s using the connections he’s made from his career in Los Angeles to do it. As an entertainer, his heart never left the farm, and his true passion lives in raising sheep and bringing agriculture into the future for the benefit of his neighbors and all local farmers.

“Ag has always been in my heart,” he said. “A lot of these barns have sat empty for 10 or 15 years. It brings me a lot of joy to see this farm alive again. My grandmother will be 96 in a couple months. She talks about the farm coming alive. She said, ‘Your grandfather would be really proud to see these barns used again.’”

As to whether the call of Tinseltown has any sway on Dotterer now, he said he will still be able to travel and visit to work on his AR project, but his roots are still on the farm.

“This is where I belong, and this is where I’m planning to stay,” he said.